In recent decades, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers have increasingly recognized the importance of children’s development during the preschool years. Children who are healthy and ready for learning when they start school are expected to achieve greater educational success and be better prepared for the challenges of adulthood. Significantly, it has been widely recognized that cognitive achievement is not sufficient for children to be considered ready for school, and that social skills, self-regulation, and physical and mental health are all essential components of being ready for life and learning.

The National School Readiness Indicators Initiative, for example, identified five domains of school readiness: language development and literacy, cognition and general knowledge, approaches to learning, physical well-being and motor development, and social and emotional development. Similarly, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is working with Child Trends to develop a measure of Healthy and Ready to Learn that takes a broad view of the competencies and developmental strengths needed to be ready for kindergarten, including the following: early learning, socioemotional development, self-regulation, and health and motor development.

However, while the preschool years have gained recognition as a critical developmental stage, only a few studies have assessed the long-term implications of preschool interventions by following children into adulthood. Available studies (such as the Perry Preschool Project in Ypsilanti, MI and the Abecedarian Project in Orange County, NC) tend to focus on interventions that have been implemented in one city or community. To assess how later-in-life outcomes might improve if children started school healthier and more ready for school, we used the Social Genome Model (SGM) microsimulation model to explore the long-term benefits of better preparing our nation’s children before they begin formal education.

In this brief, we describe the Social Genome Model and review how we applied the SGM to simulate the long-term effects of preschool interventions later in the lives of children who receive these interventions. We then describe our simulated findings for five outcomes and share effect sizes across racial, ethnic, and sex groupings. Finally, we discuss important considerations for other researchers and outline how further simulations could expand the knowledge base on the effects of early interventions on later-in-life outcomes.

Healthy and Ready for School and Life

Children with emotional, physical, cognitive, and social well-being are more likely to succeed in the education system, which yields lifelong benefits. This analysis assesses the long-term benefits of improving children’s readiness for school and life prior to their entry to kindergarten.

Using the Social Genome Model, a powerful new simulation tool, we simulated receipt of interventions during children’s preschool years by improving an array of outcomes related to well-being at age 5, and then assessed the effects of these improvements on children’s subsequent outcomes. We find that improving children’s school readiness notably enhances their outcomes in elementary school and is associated with modest but important improvements in outcomes in young adulthood, including bachelor’s degree attainment and earnings. However, the simulation did not find substantial reductions in disparities by race, ethnicity, or sex. It is important to note that this simulation focused solely on interventions in the preschool years and did not include additional interventions in subsequent years that might have boosted later outcomes.

These results indicate that interventions during the preschool years that help young children become more healthy and ready for school and life could pay dividends in the long run. Results also suggest the value of ongoing interventions and support once children enter school.

Context and Research Approach

Decades of research indicate that children who enter kindergarten with stronger school readiness go on to have greater academic achievement in elementary and high school. For example, young children with lower levels of school readiness are more likely to be retained in grade or suspended in elementary school—experiences that can greatly influence their subsequent academic trajectory. Unfortunately, a host of contextual factors contribute to long-lasting disparities in children’s school readiness. These include socioeconomic conditions such as poverty and the neighborhood in which a child grows up. If states increase access to effective programs and practices that improve preschoolers’ development, they could make significant strides toward ensuring that children are healthy and ready for school and life.

Social Genome Model Analyses

To quantify the long-term benefits of children being better prepared for the expectations of school and life, we used the Social Genome Model (SGM) to project how children’s outcomes might change later in life if all children started kindergarten healthier and more ready for school and life.

The simulation examines the potential effects of services, resources, and programs provided during the preschool years—which affect whether a child is ready for school at age 5—on children’s outcomes in elementary and middle school, and into adulthood.

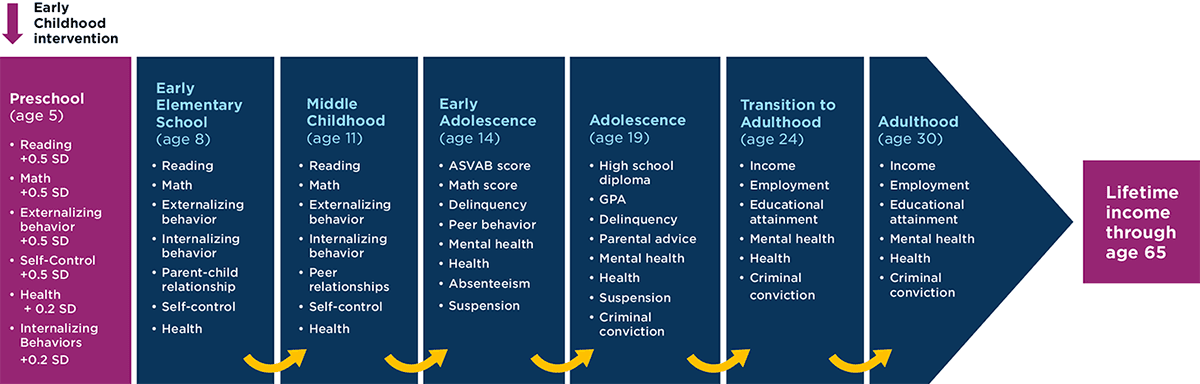

To do this, we improve the markers of school readiness at age 5 in our model, assuming that these result from enhanced interventions during children’s preschool years. To estimate the degree to which markers of school readiness at age 5 might be expected to improve if children receive an intervention in the preschool years, we drew on studies (both individual evaluation studies and meta-analyses of multiple studies) of programs aimed at preschoolers (see Appendix A for a full list of studies reviewed). In these studies, we identified a range of program effects on selected markers of school readiness: math test scores, reading test scores, externalizing behavior, and self-control. The largest improvements in these age 5 outcomes reported by the studies were 0.5 standard deviations. This is generally, although not always, considered a “moderate” effect size; however, it is larger than often found in evaluation studies. For two additional markers of being healthy and ready for school and life—health and internalizing behavior—we instead assumed that children would have improvements of 0.2 standard deviations because we did not identify studies with stronger impacts. We view these changes in the markers of school readiness as aspirational improvements, given that not all preschool programs have been able to achieve such large changes for their participants. In other words, our simulation assumes that accessible and high-quality interventions for preschoolers will increasingly be implemented by states, schools, and communities, thereby enhancing children’s outcomes at around the time they begin kindergarten.

After changing outcomes at age 5 to represent the assumed effects of attending a program during the preschool years, we observe how those changes might affect outcomes at all subsequent life stages (see Figure 1). At age 8 (early elementary school) and age 11 (middle childhood), we examine reading and math scores, internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior, self-control, and physical health. At age 30, we describe educational attainment and earnings. We also project lifetime earnings through age 65, based on education and earnings at age 30. All outcomes are net of variables included in previous stages.

Note: For all figures and tables in this brief, the White and other race group includes a small percentage of people who identify as Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander, or more than one race; because of sample size constraints, the SGM cannot estimate simulations separately for this group.

Figure 1. Visualization of the school readiness simulation in which improved outcomes at preschool ripple throughout the life course

Note

However, we cannot ignore the historical context in this simulation: Notably, historical and contemporary social, political, and economic factors restrict school readiness and lifetime opportunity for some ethnic and gender groups and boost them for others. In response, we have stratified our simulations by race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, and White) and by sex (male, female) to account for these factors and to identify the extent to which large-scale interventions to make children more ready for school have different effects for different children, and to estimate whether such interventions could address disparities in the long term.

Findings

We find that improving children’s school readiness notably enhances their outcomes in elementary school and is associated with modest but important improvements in outcomes in young adulthood. Since the hypothetical interventions are only implemented during the preschool years, with no subsequent “booster” programs at any other age, the magnitude of the initial effect inevitably declines as children age. Thus, effects on later-in-life outcomes—attainment of a high school diploma, earning an associate degree, earning a bachelor’s degree, yearly earnings at age 30, and lifetime income at age 65—are more modest than earlier life outcomes. The tables below show the effects of the simulation in absolute terms, as well as its effectiveness in reducing disparities across racial/ethnic and gender groups.

Early elementary outcomes (age 8)

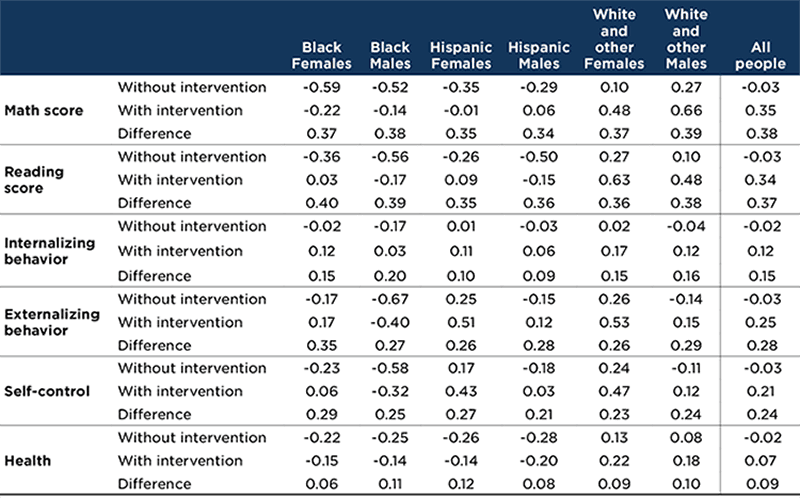

We found that elementary-age students are positively affected by preschool interventions to enhance school readiness. Table 1 depicts students’ scores for each age 8 outcome measure in the absence of intervention (Without intervention) and with intervention (With intervention). All outcomes are standardized, so a negative “Without intervention” score indicates that the average score was below the mean. The Difference row in the table reports the magnitude of the change in the outcome for each of the six race/ethnicity/sex groups.

Given that the simulation intervenes across a broad array of domains, improvements in children’s well-being are broad. That is, children who enter kindergarten healthier and with greater pre-academic and social skills experience notable improvements by age 8 in math, reading, internalizing behavior, externalizing (acting out) behavior, self-control, and health status. That said, the changes are smaller than the 0.5 that is simulated; this is expected because changes tend to wear off over time. The changes in health are rather small, reflecting that the simulation modeled just a 0.2 effect size. These improvements were found across all race/ethnicity and sex subgroups, with one of the largest improvements in internalizing behavior seen among Black males.

Table 1. Simulated early elementary (third grade/age 8) outcomes resulting from improved school readiness

Note

Middle childhood outcomes (fifth grade/age 11)

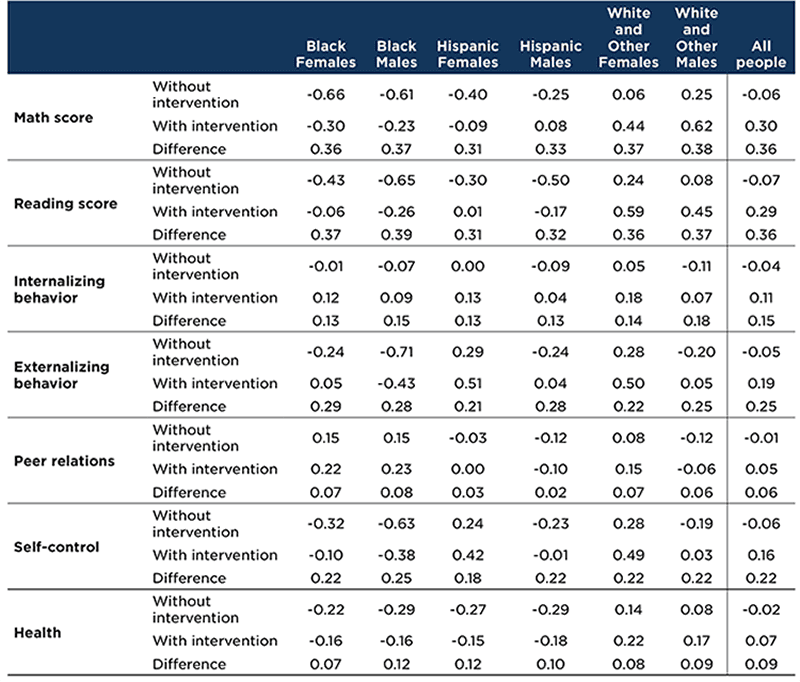

We found, further, that improvements in outcomes continue from age 8 into middle childhood (about age 11), with better math and reading scores and better ratings on internalizing and externalizing behavior, self-control, health status, and peer relations. While the simulated improvements are often not sufficient to bring the negative (below average) scores into the positive (above average) range, enhanced outcomes were found across all race/ethnicity and sex subgroups.

Table 2. Simulated middle childhood (fifth grade/age 11) outcomes resulting from improved school readiness

Note

Educational attainment

Our analysis showed modest increases in high school graduation by age 24 (see Table 3). This reflects the likely diminution of effects over time, given that no booster programs are provided in the simulation. This effect could also reflect a limitation of the Social Genome Model itself, because there is some loss of continuity when ECLS-K cases are matched with NLSY97 cases to form the synthetic cohort. The increases found at age 24 range from less than 1 percentage point to 1.6 percentage point.

Increases in associate degree attainment by age 30 range from no measurable increase to a 1 percentage point increase; however, since the baseline proportion of the population who had an associate degree prior to the intervention ranged from just 5 to 14 percent, a 1 percentage point increase is not trivial (Table 3).

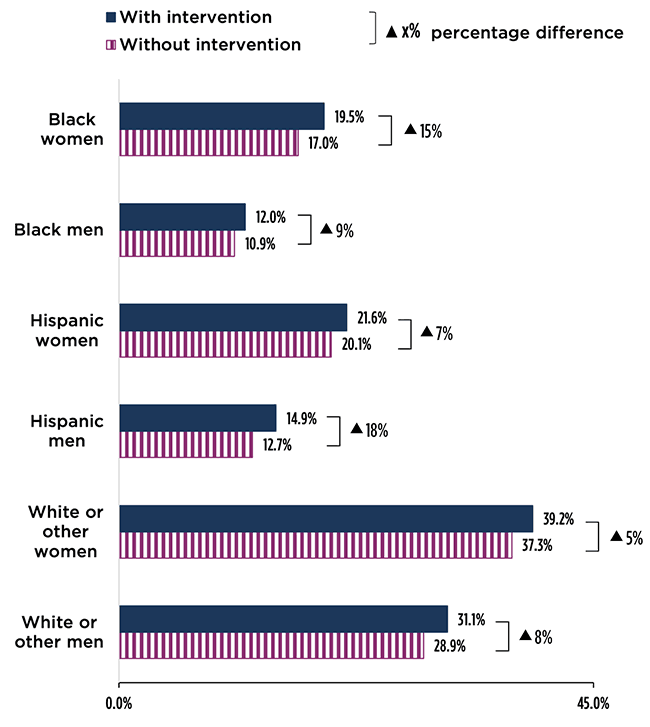

Educational increases in attainment of a bachelor’s degree by age 30 are also modest but notable, with increases of 1 to 2 percentage points (Figure 2). Although 29 percent of White men and 37 percent of White women had college degrees in the absence of intervention, the proportions were much smaller among young adults of color. Specifically, the percentage with a bachelor’s degree was 17 percent among Black women, 20 percent among Hispanic women, 11 percent among Black men, and 13 percent among Hispanic men. Given these initial levels, an increase of 1 to 2 percentage points is noteworthy. For example, Black women would experience a 2.5 percentage-point increase (a 14.7% relative increase), with even more pronounced relative gains for Hispanic men, at 2.2 percentage points (a 17.6% relative increase).

Figure 2. Improving children’s school readiness increased bachelor’s degree attainment for all demographic groups in our simulation

Simulated increase in bachelor’s degree attainment by age 30, by race/ethnicity and sex

Note and Table

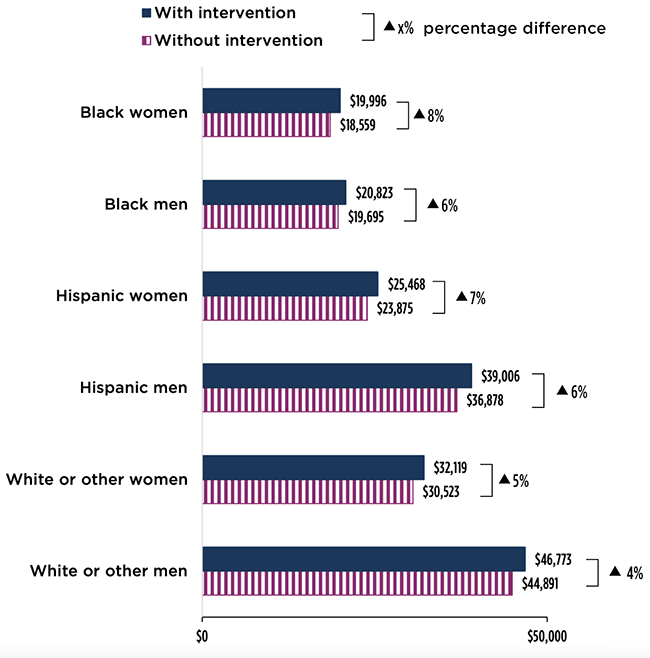

Yearly earnings (age 30)

We found small increases in earnings at age 30. In addition to the importance of education and training, research increasingly finds that a variety of competencies and personal strengths contribute to labor market success. Accordingly, we examined the effect of this simulation on earnings at age 30. As shown in Figure 3 and Table 4, the simulation indicates annual increases in income of about $1,400 to $2,100 at age 30. Hispanic men would experience the greatest increase in earnings at age 30 ($2,127). However, Black men and women and Hispanic women had greater relative increases in their earnings. Nevertheless, absolute earnings increased more for the highest-paid group (White men) than for the lowest-paid group (Black women). This indicates that, even if all children started school healthier and more ready for school, existing disparities in later life earnings would persist in the absence of subsequent interventions.

Figure 3. Improving children’s school readiness increased annual earnings at age 30 for all demographic groups in our simulation

Simulated increase in age 30 annual earnings, by race/ethnicity and sex

Note and Table

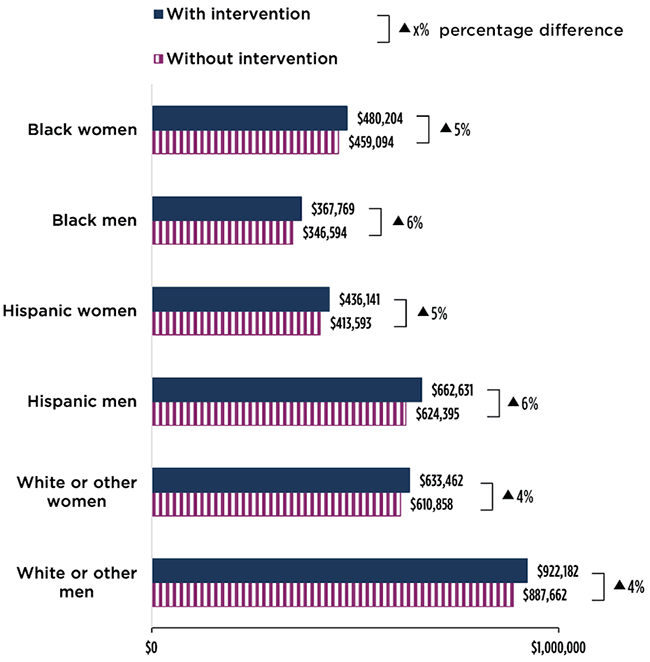

Lifetime earnings

We also found a small increase in lifetime earnings. For lifetime earnings, we found a pattern similar to what we found for age 30 earnings. Figure 4 and Table 5 show the present value of lifetime earnings using an interest rate of 2.6 percent. Earnings are discounted using this rate since the value of present earnings is higher than the value of future earnings due to potential investments (i.e., money invested today receives a higher payoff than money invested later). As shown below, the gains in discounted lifetime earnings range from $21,109 to $38,237. (Undiscounted lifetime earnings would be approximately twice as large.) The simulations suggest that Hispanic men would see the greatest increase in lifetime earnings, with an estimated $38,237 increase (the equivalent of more than a year of pay at baseline). Relative increases were 6.1 percent for both Hispanic men and Black men.

Figure 4: Improving children’s school readiness increased lifetime earnings for all demographic groups in our simulation

Simulated increase and percentage increase in lifetime earnings, by race/ethnicity and sex

Note and Table

Conclusions

We found that efforts to help preschool children meet expectations for entering kindergarten could pay dividends in the long run across an array of outcomes. Improvements in educational attainment, such as the attainment of bachelor’s degrees, could make a considerable difference when achieved at scale—for example, in enhancing annual earnings and improving the quality of one’s personal, family, and civic life. Notably, Black and Hispanic men and women experienced the greatest relative growth in the outcomes of high school degree attainment, associate degree attainment, bachelor’s degree attainment, and yearly earnings. However, we did not find that school readiness interventions alone substantially reduced prevailing disparities in lifetime earnings, and additional interventions and structural changes to address racism and sexism will be necessary to achieve race and gender equity.

Limitations

As with all research based on microsimulations, this study has a number of limitations that users should consider when interpreting its findings. First, the Social Genome Model is not a causal model and cannot be used to make causal conclusions; therefore, all simulations should be considered as potential scenarios. Second, all regressions underlying the model are linear; the model does not account for any path that can lead to quadratic or cubic effects, or any non-linear path. Third, the longitudinal data used are older by design in order to have data through age 30 and may not fully represent the characteristics of children and youth today. Finally, all the benefits are quantified for individuals, and not for society.

Considerations for future research

This research demonstrates the practical application of several conceptual and research innovations. First, the multidimensional nature of this simulation builds on the important understanding that success in school and life is strengthened by a broad array of competencies. By improving children’s well-being across varied domains, we found notable improvements in later-in-life outcomes. This demonstrates the utility and importance of efforts to help all children be healthy and ready for the expectations of school and life.

Second, this simulation focused on interventions for preschool children, assuming that these interventions enhance an array of outcomes at age 5. The subsequent provision of services and programs would undoubtedly sustain and enhance the outcomes we find here. Thus, while preschool interventions are important, high-quality and accessible interventions for school-age children and youth are needed to sustain and build on preschool success.

Third, our analyses have focused exclusively on individual-level benefits. While important, there are also numerous benefits to society and families associated with higher levels of education and earnings.

Fourth, as mentioned above, we found notable gaps in the evaluation research despite the existence of several long-term evaluation studies. Rigorous long-term assessment of interventions that seek to enhance and then assess effects for a variety of outcomes—including cognitive development, health, social and emotional competencies, and self-regulation—would strengthen the knowledge base. Also, while the longitudinal data in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Surveys and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth have made it possible to update the SGM and follow children and youth into early adulthood, we acknowledge that the data used to build the SGM are becoming dated. Implementing new longitudinal surveys in the coming decade that capture demographic and socioeconomic changes in the U.S. population would enable new research and allow for ongoing strengthening of the Social Genome Model.

Finally, we note that future research could follow the lines of our simulations using the Social Genome Model—connecting results from policy innovations and program evaluations to large-scale and long-term outcomes.

Learn more about the Social Genome Model, a partnership between Child Trends, the Brookings Institution, and the Urban Institute.

Appendix A: List of Studies of Preschool Interventions Reviewed

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram